EB-5 投资者 EB-5 基础知识

EB-5 中的老龄化问题

Last Updated: 11 月 5, 2025

Under the Immigrant and Nationality Act, each EB-5 petitioner is eligible to apply for immigrant visas for a spouse and any unmarried children under the age of 21. The inclusion of the applicants’ family on a single EB-5 petition is the reason why every EB-5 petition is considered an application for multiple visas. Each of the petitioner’s unmarried children under the age of 21 are eligible to join the petition, which is favorable to investors who wish to educate their children in the U.S. and provide them with a wide range of employment opportunities. In fact, many EB-5 investors opt into EB-5 for the benefit of their children.

However, the ability to include children on an EB-5 petition expires once the child becomes 21 in the eyes of the law. This makes a relatively straightforward privilege incredibly complicated and pressing for immigrants, as the current visa backlog that affects many applicants from China, India, and other countries has caused countless dependent children to age out. With a backlog predicted to last more than 8 years, an applicant’s children may surpass the age limit and lose their visa privilege in a lesser-known process called “aging out”.

How is the age of a child calculated for EB-5 purposes?

The US government is well aware of the visa backlog problem and the processing delays faced by immigrant petitioners, and aging out quickly became an issue across all visa categories. Therefore, in 2002 the U.S. Congress passed the Child Status Protection Act (CSPA) to address the problem of “aging out” and to protect the dependent children trapped in the quagmire of bureaucratic delays.

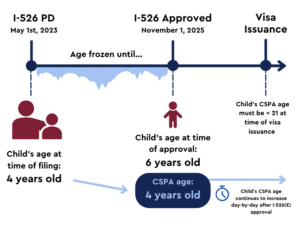

Under the CSPA rule, a child’s age is “frozen” while the first immigrant petition is pending at USCIS. In EB-5, their age is frozen on a petitioner’s I-526 priority date. However, once the first petition is approved, the child’s age “unfreezes”, and under CSPA protections, the child is still legally considered the same age as when the petition was filed. Every calendar day that passes after the first petition approval is added to the child’s CSPA age.

For example, an applicant who files an I-526 for themselves and a four year old child on May 1st, 2023 would “freeze” their child’s age as of May 1st. If the petition is approved in November 2025, the child would still be legally considered four years old, but would no longer have their age frozen. Therefore, the following year, the child would be considered five, and so on.

The family must “Seek to Acquire” lawful permanent resident status, which entails paying the visa fee bill and any other fees owed to USCIS or the NVC, as well as submitting part 1 of the DS-260 online visa application (within a year of visas becoming ‘current’, meaning visas are now available for the petitioner’s EB-5 priority date). If these conditions are fulfilled, the family can freeze their child’s CSPA age on the first day a visa becomes available for their approved I-526(E). If the above process freezes the child’s CSPA age under 21, then the child can complete their consular processing for an immigrant visa without fear of aging out. However, if the family for any reason does not, or cannot, “Seek to Acquire” before the child’s CSPA age reaches 21, the child will no longer be eligible for inclusion on their parent’s visa.

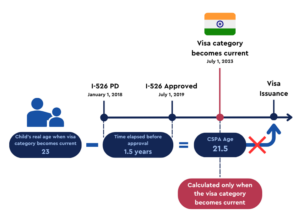

This process is made more complicated if there are no visas currently available to petitioners based on their nationality (AKA the petitioner occupies a “backlogged” category). For example, Chinese and Indian applicants, who face an incredibly long backlog on the visa bulletin, have constraints on when CSPA age can be re-frozen after I-526(E) approval. Their CSPA age cannot be re-frozen until their visa category becomes current (meaning visas are now available for the petitioner’s EB-5 priority date and for their nation of birth). When a category becomes current, the EB-5 investor and family can pay the Fee Bill and file the DS-260 form, to satisfy the “Seek to Acquire” requirement. Doing so will freeze the child’s CSPA age again, through to the end of the consular process.

Thus, a waitlisted EB-5 investor must:

1) subtract the days of I-526(E) adjudication from their child’s age; and

2) add the days after I-526(E) adjudication to their child’s age, up until

3) the date that they fulfill the “Seeking to Acquire” conditions, whereupon their child’s age freezes again for the rest of the consular process. The resulting number is the child’s CSPA age.

Take the example of an Indian petitioner applying for a backlogged EB-5 category with their child as a dependent applicant. If a petitioner’s priority date is January 1, 2018 and the I-526 form is approved on July 1st, 2019, there are 1.5 years which will be subtracted from their child’s age once the visa category becomes current. Hypothetically, if the Indian EB-5 category became “current” on July 1, 2023, 1.5 years would be subtracted from the child’s REAL age at that time. If the child is 23 at this time, their CSPA age would then be 21.5.

23 (child’s age when visa category becomes current) – 1.5 (amount of time between PD and I-526 approval) = 21.5 (CSPA age)

In this example, the child’s CSPA age is over 21. This means that the child is no longer eligible for a visa on their parent’s petition. In some cases, CSPA provides relief for many immigrants across all visa categories, but as shown by the example above, many immigrants continue to suffer from “aging out”, even with CSPA protection.

The goal of CSPA is to alleviate the effects of long processing times at USCIS—which has remained a significant problem for decades. However, CSPA does not address the problem of visa backlog. Unprecedented delays and government inefficiencies make the problem of children aging out far more severe than exceptions like CSPA can prevent against. This means that a child can be separated from their parents, and often leads EB-5 immigrants to forgo their current petition and investment in favor of an immigration option that keeps families together.

As discussed in previous AIIA blogs on visa backlog, the combination of per country caps and the minimized unreserved EB-5 allowance has resulted in many applicants receiving priority dates more than 8 years away from the date when visas may become available to them. Unless USCIS were to dramatically alter their operations and efficiency in processing petitions, children will continue to age out while petitioners wait for their visa category to become current.

Recent change in USCIS policy

USCIS issued a policy memo in February 2023 highlighting a change in the interpretation of CSPA age calculation. This particular change concerns how USCIS determines when “a visa becomes available”. Traditionally, the Department of State (DOS) uses the Final Action Dates in Chart A of the current visa bulletin to determine visa availability. However, due to how USCIS typically operates and no prior court ruling on the matter, USCIS will now determine visa availability based on when a particular investor can submit their I-485. Which means, Chart B’s Date of Filing could also be considered as the day when a visa becomes available.

It is important to note the DOS issues monthly updates on whether it is using Chart A or Chart B for the purpose of accepting I-485s, which means Chart B’s Date of Filing is not necessarily the day a visa becomes available for every EB-5 applicant. Information on which chart the agency is currently using is listed on the visa bulletin website. While USCIS has begun implementing this policy change, U.S. consulates around the world—all which fall under the oversight of the DOS—have not embraced this change yet. It is expected that the two agencies will soon reach a mutual understanding, as to avoid unnecessary inter-department complications. Yet no such agreement has been brought forth yet.

This development is good news for EB-5 investors and their children, as the dates on Chart B are generally earlier than those on Chart A. In other words, the age of an EB-5 applicant’s child will “freeze” earlier when USCIS is using Chart B as indication for I-485 filing. Although this change does not tackle any institutional problems related to the source of the visa backlogs, the change still offers some relief for EB-5 applicants whose children face the risk of aging out.

In conclusion, the age of an EB-5 applicant’s child is determined by both their age at the date of visa availability and the time it took USCIS to process I-526. Calculating a child’s CSPA age is somewhat complex, but can easily be determined with the help of legal counsel, and should be discussed early on in one’s immigration process. Furthermore, USCIS has taken a step in the right direction by adopting a more lenient interpretation of when a visa becomes available for a child. However, compared to the significant challenges of the visa backlog, these micro changes are incapable of resolving the underlying problems behind the backlogs—just like putting a band-aid on a bullet wound.

针对 EB-5 投资者

更多资源

找不到合适的资源

请使用此工具找到最适合您需要的 EB-5 资源。

联系我们

如果您有任何问题、咨询或合作建议,请随时联系我们。